“…WHILE MOSCOW HAS THE MOST BILLIONAIRES IN THE WORLD, 25% OF THE CITY LIVE BELOW THE MINIMUM WAGE…”

There are two Moscows, one which is official and the other, in the shadows and hidden from view. One could argue that Moscow is governed with acute awareness of the reality of what the city actually is; recognising the the official Moscow, whilst ignoring and missing out on the opportunity of taking account of the ‘other’ Moscow.

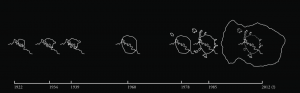

EXPANSION

Apparently, Moscow is expanding. On June 17, 2011 Dmitry Medvedev proposed to expand Moscow’s borders and to create a new Moscow federal district (Al-Jazerra 2011). Shortly after, Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin announced that the city’s territory would be expanded by more than two

times (by 144,000 hectares or 356,000 acres). In August 2011, a draft proposal for Moscow’s expanded borders was released, and in January of

2012 the contestants announced of an international competition to propose

a development concept for the new federal district (Al Jazerra 2011). This decision – in essence, an attempt to find a tabula rasa to build a ‘new city’ – is declared publically to be aimed at easing the dependency on the core of central Moscow (relieving the center of the city) by creating new financial and moving governmental functions in the new territory as incentives for the development of workplaces.

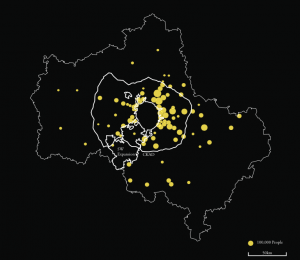

Although in the past Moscow has expanded to its infrastructural boundaries radially (firstly from the Boulevard Ring to MKAD ring road in 1961), the new administrative region of Moscow city will not expand to the next ring road (the CKAD; currently under construction); nor have the authorities proposed to merge Moscow City with Moscow Region. Instead,new boundaries were drawn to new borders to the southwest of the existing Moscow City territory. According to the Moscow City Government website, the southern and southwestern outskirts were chosen in part because they comprise “a relatively weakly urbanised sector of the Moscow region” (Moscow City Government 2011), counting some 250,000 people. Essentially, the redrawn borders were

chosen to include the least amount of people into Moscow Federal District,

or in other words, to exclude the most amounts of people from gaining the benefits of which a Moscow Citizen currently receives. The borders were later revealed to be drawn by the Ministry of Finance; with the aim that the tax- revenues receied from the addition of the new territory would be lower than that which would have to be paid out to the “new Muscovites” which would

be captured by the expansion. In making a decision of exclusion, the redrawn territorial borders do take into account the economic contribution to Moscow of those who either currently reside outside and commute into the city or those who are not yet registered as official residents of Moscow City. The expanded territory is to be precisely in the area of the Oblast which makes the least contribution to the problems which an expansion could actually relieve.

In the press-conference to announce the expansion, Mayor Sobyanin proclaimed proudly that “We are not only going to keep the present social policy standards in the capital, but improve them annually, and this includes

the handicapped. This is because one of our basic programs is the provision of social support to Muscovites” (Adamova 2011). Consequently in January 2012, the Department of Social Security of Moscow City Government announced that “from July 1 2012, social benefit recipients residing in areas that are to become part of Greater Moscow will be entitled to all benefits currently paid in Moscow City”. The new territory would pick

up an additional 250,000 extra social benefit recipients which, based on an average social benefit spendings of $1600 USD per month (as opposed to $800 USD in Moscow Region), would add approximately $400m USD in additional social expenditure per year (Moscow City Government 2012). However, this spending is offset by the project $1bn tax revenue to be captured when the region is incorporated into Moscow City. Thus, the Moscow budget receives a windfall surplus revenue of $600m

Whilst if Moscow City were to be expanded to merge with the territory of the CKAD, then an extra $4bn in taxation revenue will be captured. However, by the same calculations, an extra 5m Muscovites have to be eligble for the same social spending, increasing spending to $8bn USD. This leaves a budget deficit of an extra $4bn in extra spending for the CKAD expansion; a significant cost over the SW zone expansion. Furthermore, due to an aging population, calculations by Renaissance Capital project that unless the retirement age is raised, spending on pensions will need to expand by a third in real terms over 2011- 2030 (Tong 2011). As social support is currently the second largest expenditure (after transport infrastructure) in Moscow’s budget, the decision to the draw new borders borders in the SW zone to include as little extra persons as possible, appears to be driven, at least in part, to mitigate the added burden of an increased social security expenditure.

The decision to expand Moscow to a new territorial zone which deliberately excludes the most amount of additional citizens implies a short-term decision making goal within the Moscow authorities to limit the amount of social expenditure in order

to cut-costs. However, by limiting the expansion zone, it is also limiting its responsibility and scope to deal with effectively the full extents of economic contribution to Moscow, again adding to the Moscow’s inherent inequality.

INFORMAL ECONOMY SECTORS

The following section does not aim to provide an exhaustive scientific empirical study of the complete size of the informal economy in Moscow. Rather, by selecting various informal activities which are well known to Muscovites

and showing their size, the aim is to reveal their importance to how the city functions.

Gypsy Taxi

There are approximately 50,000 taxis in Moscow, of which 40,000 are not licensed (Kostina 2011). Average monthly revenues per car range from $1000 – $3000 p.m. (from interviews).

Shuttle Trading

Shuttle trading accounts for aprox. 1/4 of Moscow’s imports of goods (Yakovlev 2006). Total imports of goods 2011 $115.5bn. Shuttle traders report revenues of ~30% of value of imported goods.

Markets

There are 50 semi-regulated markets which contribute an estimated 18% of Moscow annual retail turnover (Cherkizon 2009).

Sex Work

There are aproximately 200,000 sex workers in Moscow, ranging from high- class escort services to street-workers. Each earn around $2000 per month (some more and some less) (Sky 2011).

Bootleg Alcohol

Illegally produced alcohol acconts for aprox. 60% of total sales. Average alcohol consumption per person per year 18lt. Minimum price standards at $3/lt. (Time 2009)

Casino

July 2009, Federal Gov. bans all casinos across Russia (except 4 provinces). Reports that up to 80% all gambling has moved underground. 2008 the legal gambing industry was $1.8m. (Ria Novosti 2011)

Waste Disposal

Moscow produces 39m tonnes of waste per year of which only 50% is properly accounted for (Wikileaks 2008). The rest is dumped in illegal landfills. The aproximate ‘cost’ for illegal dumping is $200 per tonne

Illegal Construction

Whilst likely to be understated, 431,200sqm of illegal construction activity was reported in 2011 with an average cost of (housing) construction at $2000 psm (Rosstat 2011).

Pornography

S.242[2] Russian criminal code: “prohibiting sale and distribution of pornographic materials.” Estimates are that the Moscow porn industry generates $100m in revenues per month (Der Spigel 2011).

llegal Billboards

80% of all outdoor advertising is illegally placed. 2011 total outdoor advertising value, $380m (Moscow News 2011).

Informal Microfinance

UNDP estimates external informal finance equivalent to 1.8% of Moscow GDP ($495bn). (UNDP 2011)

Kiosks

There are aproximately 20,000 kiosks in Moscow, of which only 20% have the proper operating licences. The average annual turnover is aproximately $330,000 depending on location. (Moscow News 2011)

Whilst the above sectors are not a fully scientific study of the informal economy in Moscow, they all represent conservative estimates of what each sector could be. Taken as an aggregate, they represent a $47bn industry sector, which would be the largest non-resource based company in Russia. Whilst it is obvious that these sectors are already productive, the operators who are in the informal sphere are caught in a trap that places boundaries on how a business can develop. Although informal systems provide a means for enterprise survival, they do not support the growth of enterprises in a legitimate way and by remaining informal they inherantly remove capital from the formal economy impeeding the ability of the state to provide proper services to its citizens.

While this paper attempts to show that informal economy in Moscow is already a very large and productive informal sector, it should not be mistaken for an argument for further unbridled liberalization. Working in the informal economy means that the operators are working outside a proper regulatory legal frame work, and hence are unable to fix and record assets in order

for entrepreneurs to access credit to grow their businesses. The majority of operators in the informal economy cannot make the market work to their advantage because they are fragmented in non–specialized groups where “labor cannot be divided efficiently and where they lack the means to define, benefit from or enforce economic rights” (De Soto 2000). In Moscow’s “extralegal world,” only the elite are able to create wealth, thereby generating frustration among those outside the “system” (Bain 2007).

Despite liberal economic theory that envisions the market as eliminating

biases in the allocation of resources, due to the hasty liberalisation process; discriminatory extra market forces have operated, restricting access to resources. For those working outside of the law, informal, or extralegal assets become dead capital when cannot be used effectively for economic transactions, guarantees, contributions or compensations (De Soto 2000). For operators

in the informal economy, a lack of proper accounting processes, transactional recording, legal working conditions create a climate where informal operators are unable to access credit or external capital in order to grow their businesses (De Soto 2000). The effects of instability in the Russian economy has increased the risk to banks and financial institutions of loaning money; substantial collateral is demanded in order to receive credit and has resulted in significant interest rates charged, ranging from 20-25% p.a from Nikoil bank and the National Development Bank (Bain 2007). Correspondingly, Among newly established firms, only one in ten manages to get bank loans, and five times as many borrow from private sources. one in ten start-ups to get bank loans, and

five times as many borrow from private sources (Polishchuk 2002)

Significantly however, demands of a proper registration and residency permit are an impediment to many merchants in the informal

economy – hence, only one third of Muscovites (who work in the non-government sector) have a bank account (Pravda 2004).

Consequently, we see the rise of many micro- finance options, of which flyers litter many metro station entrances. These services are provided by individuals who have the necessary requirements to borrow money from a legitimate bank, after which the money is subsequently lent to the final borrower. A call to a micro-lender asking for

a $2000 loan revealed that the terms were that $4000 would have to be paid-back after 6 months.

Viable credit is not available to entrepreneurs who operate in the shadow economy, consequently they will always be excluded from opportunities to develop a fully legitimate enterprise (De Soto 2000).

TRACKING MONEY FLOWS

As a closer examination into the micro-economy of firms in the informal sector, the Russian phenomenon of shuttle trade (or челноки) was closer examined. Aproxmately 50% of the price of a product sold in a market is due to bribes to circumvent inoperable laws.

the cost of buying goods, includes the following items: payment for the “shop-tour”, cost of transportation of goods, rental for a retail outlet, wages paid to a hired salesperson include travel expenses and cargo agents.

Travel Expense. Shuttle traders typically pay a fixed cost for a ‘shuttle tour,’ who arranges the trip. Usually a fixed ammount aproximately $300-$400 for a single 3-4 day trip (Yakovlev 2006). Naturally, depending on starting and end point.

Cargo Agents. Though in mid-90s there still remained traders who carried their cargo in-flight, today, typically the mechandise is offloaded to cargo ‘agents’ who pay-off custom’s officials to underreport cargo and thus avoid excess customs-tariffs. Typically 20% of worth. (Yakovlev 2006)

Whilst taxes are not paid (or the less than full ammount paid when underdeclaring goods),

a significant ammount of the product costs is associated with circumventing the law (shown in red). At the mark ets, krysha is paid to ensure that local police do not hassle traders, and for taxation officials not to investigate. Cargo agents pay customs officials to under-declare the goods imported. (Yakovlev 2006).

In 2006, customs were further restricted that only $2000 worth of goods were allowed to be brought in to discourage shuttle trade. Whilst this had the effect of slightly reducing the amount of shuttle trade, Yakolev (2003) claims that this merely increased the payments made to custom’s officials in under-reporting.

Coinciding with the liberalisation of the Russian economy, the rise of small- scale wholesale open-air markets was closely related to the phenomenon of “shuttle” imports of consumer goods, which emerged on a massive scale in Russia in the early and mid-1990s. Shuttle trade is the phenomenon of traders who shuttle back and forth between major port cities (outside of Russia) buying goods from cheap sources and selling them back in Russia.

Whilst its peak was in the mid-90s, it still happens to an extent. According to some estimations, up to 10 million Russians were engaged in shuttle business at all its stages (Yakovlev 2006). It is estimated that the size of shuttle trading is equivalent to 1/3 of Russian imports (IMF 2007).

In the 90s, permission to import goods for up to $5000 duty-free was given to physical persons and made the legal base for this success.

Whilst shuttle trade were blamed practices leading to taxation payments and customs duties not reaching state finances, due to the inherantly long supply chain, it is also recognised for the economic and social benefits which it provides to a number of participants. The practice of shuttle trading not just provides economic benefits to the traders themselves but also the organisation of shop tours, transportation, storage and sale of goods at wholesale markets and in retail trade.

While on a field trip to Izmaylovo market and The All-Russia Exhibition Centre, several of the traders confirmed that their goods were supplied by shuttle traders, with the goods many Moscow originating from a key transit point from Laleli market in Turkey. The reason that Laleli market appears to have gained prominence is due to two factors; a relatively easy visa-on-arrival availiable to Russian citizens, and its proximity to Moscow. While, traders were not more forthcoming or knowledgeable, this initial observation is backed by

a report (Yakolev 2003), which follows money flow through various supply chains (illustration below).

Traditional structure of business expenditures in the “shuttle business”, aside of

the cost of buying goods, includes the following items: payment for the “shop-tour”, cost of transportation of goods, rental for a retail outlet, wages paid to a hired salesperson include travel expenses and cargo agents.

Travel Expense. Shuttle traders typically pay a fixed cost for a ‘shuttle tour,’ who arranges the trip. Usually a fixed ammount aproximately $300-$400 for a single 3-4 day trip (Yakovlev 2006). Naturally, depending on starting and end point.

Cargo Agents. Though in mid-90s there still remained traders who carried their cargo in-flight, today, typically the mechandise is offloaded to cargo ‘agents’ who pay-off custom’s officials to underreport cargo and thus avoid excess customs-tariffs. Typically 20% of worth. (Yakovlev 2006)

Whilst taxes are not paid (or the less than full ammount paid when underdeclaring goods),

a significant ammount of the product costs is associated with circumventing the law (shown in red). At the mark ets, krysha is paid to ensure that local police do not hassle traders, and for taxation officials not to investigate. Cargo agents pay customs officials to under-declare the goods imported. (Yakovlev 2006).

In 2006, customs were further restricted that only $2000 worth of goods were allowed to be brought in to discourage shuttle trade. Whilst this had the effect of slightly reducing the amount of shuttle trade, Yakolev (2003) claims that this merely increased the payments made to custom’s officials in under-reporting.