https://vimeo.com/114006384 [NOT WORKING DUE TO AUDIO COPYRIGHT ISSUES]

Category Archives: Samuel Shapiro

The Genesis of Form: Creating Self-Consistent Architectures

Traditionally, it was believed that form was “assigned” by the higher powers, and so the world and everything in it were created in God’s eye. But the philosopher Deleuze argued otherwise. “The resources involved in the genesis of form are not transcendental but immanent to the material itself.” A soap bubble is round and a salt crystal is cubed due to the physical and chemical properties of the molecules of which they are composed. But even more interesting are what Deleuze refers to as “spaces of energetic possibilities” (aka “state spaces” or “phase spaces”), for example in a more complex process such as embryogenesis, where “the division of the egg is secondary in relation to more significant morphogenetic movements”. Material and energy flows determine the behaviour of a substance and its resultant form at every moment – in essence, there exists a mathematics that already “knows” which form will exist at any given phase.

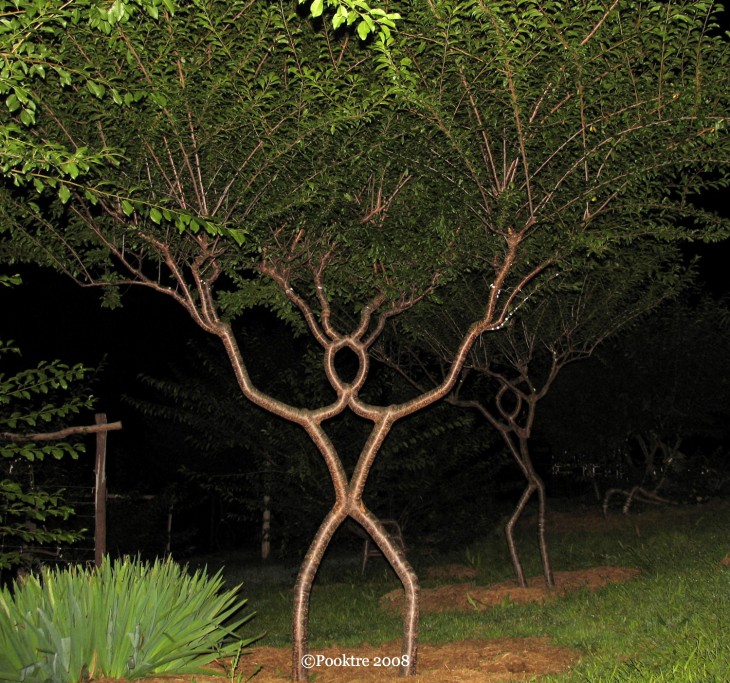

Deleuze also talks about two key structures, namely “strata” and “self-consistent aggregates” (or “trees” and “rhizomes”, respectively). A good example involves sedimentary rock, which is composed of highly ordered and homogeneous layers of pebbles, but the sorting mechanism that created this architectonic structure – flowing water and gravity – operated quite simply according to basic physical principles. Similarly, the formation of such strata can also be observed within the biological and social realms. To generalize, heterogeneous elements, when affected by a series of operators, or “intercallary elements”, organize accordingly and interlock locally, resulting in organized systems with decreased entropy.

For me, all of this translates simply to the idea that ecosystems (whether physical, chemical, or biological) always strive towards a low-entropy state – the path of least resistance, so to speak. In nature, material is expensive, but shape is cheap, and so forms will naturally evolve according to the most efficient process possible and ultimately arrive at the most efficient configuration possible. I have always been fascinated by how form is dictated by mathematics. In my mind, the human approach to design is often arbitrary, and based on aesthetics and stylistic considerations. When one looks at the amazing creations of nature, one realizes that evolution operates not according to a bigger picture, but based on low entropy mathematics which will always yield the most efficient (and often effective) result. For example, if one examines the ROLEX Learning Centre, designed by SANAA, one will realize that a lot of the design decisions are perhaps arbitrary. Why create a rectangular building with a 9 m x 9 m grid and then cut spheroidal openings into it? Why fourteen openings and not twelve or fifteen? Why this landscape pattern and not another version? However, many aspects have no doubt been carefully considered and efficiently calculated – for example, the curvature of the shells; the divisive effect of the contours, both physically and psychologically; the acoustics throughout the building; the penetration of light; the proportion of all the elements and furniture in the building; and so on. Of course, architects design buildings for people, and since people are capable of complex thought, bodily perception, and emotional experience, not to mention that our buildings must satisfy a wide array of programmes and functions, architectures for people must take these elements into account. Perhaps the mathematics of design for humans is not as simple or as objective as the mathematics of cellular morphogenesis.

Ultimately, I remain curious about developing both architectures and building processes that mimic morphogenetic qualities and remain as efficient and effective as possible throughout all phases of a building’s existence. This reminds me of Sean Lally’s “The Shape of Energy”, where architecture composed of “material energies” can change and adapt, appear and disappear instantaneously, based on climatic conditions and human needs. There is no waste and senselessness – only logic and responsiveness exist in such architectures. How can we accomplish this in the physical realm, with concrete materials? Can we transgress conventional design and instead act as guides for “self-consistent architecture”?

A New Vernacular: Building with the Intangible

Architecture has traditionally existed in the static realm, built from solid-state materials arranged in a certain configuration to arrive at a particular form. Every building has a “climax form” – that is, the originally intended geometry. This form is assertive in its territorial control, unchanging in its aesthetic, and largely unresponsive to its environment. Such architectures come across as stable and definitive, but in reality they are quite frail, because any deviation from the climax form results in failure.

In his article “The Shape of Energy”, Sean Lally advocates for a new architecture that is based on “material energies”. We are constantly surrounded by different energies – thermodynamic, electromagnetic, acoustic, chemicals – and we take them for granted, but in reality the role which they play in our lives and in influencing our behaviours are just as, if not more important, than our concrete environment. Material energies create boundaries that are fluid and responsive, resulting in a vernacular that is intimately connected to both regional and climatic conditions.

So how would one apply these intangible energies? Unfortunately, while he brings up some very interesting points, Sean Lally has failed to address the practical application of his ideations. One cannot just take energy and build with it. Humans exist in the physical domain, and we do not have a physical grasp on energy. In order to use something as a building block, one must first gain an intimate understanding of the material at hand, and while we may have an intuitive sense of different energies since we are surrounded by and interact with them on a daily basis, we are a far cry from being able to control them, not to mention manipulate them for careful study and experimentation, and eventually incorporate them into our architectural realm.

What I find fascinating is the physical manifestation of energy. Every energy somehow influences the physical environment. Tree wells form because heat generated by trees melts the surrounding snow, and compass needles point north because of the Earth’s magnetic field. Paying attention to changes in the physical environment provides information about surrounding energies as well as changes in energy conditions. A person putting on a sweater might signify a drop in temperature, while the same person, now reading a book, moving from one room to another might suggest an increase in noise or a decrease in light in the former space. By observing such changes in our environment, one can gain much insight into the invisible forces that surround us.

Another compelling thought is that architecture based on material energies would be able to adapt almost instantaneously to changes in the environment or in social programming. Through a feedback relationship between material energies and existing climatic context, an active dialogue would emerge between a building’s environment and its building blocks, with architecture that can either “dissipate on command” or respond accordingly in its shape and configuration. Of course, such a fluid reality is still far away.

It is interesting to view Sou Fujimoto’s House N in light of material energies. The house itself is purist and minimalistic, and in the physical domain it might seem like a purely spatial exercise – that is, three shells nested one inside the other. However, it is not just the walls that create an increased sense of privacy and separation as one moves deeper into the house; the change in light, sound, view planes, temperature, bodily sense of enclosure, etc. all contribute to the gradient that exists through the spaces.

I am of the strong opinion that so long as we do not transgress the physical nature of our corporeal existence, neither will our architecture. However, this does not mean that we cannot study and become more in tune with the forces that we cannot readily control, because we can certainly shape existing energies with solid-state building materials. An example that comes to mind is Philippe Rahm’s Convective Apartments, in which the architecture is designed according to the principle of convection. In this case, it is the existing thermal landscape that has shaped the resulting configuration of the building’s solid elements. Even though the architecture remains static and potentially iconic in its form, this is the first step towards an architecture informed by energy. I would be interested in examining such basic physical and climatic principles in order to generate systematic, vernacular designs that directly reflect their environmental conditions.