In 1964 Nelson Mandela was put in prison after following the idea of fighting for equality in all means.

His idea of equality and forgiveness was his main leitmotiv but their economic expectations were composed around a plan that included a lot of work to do.

His “economic dream” was based on the “Freedom Chárter”, where work and education for all, and a sharing of the vast natural resources of the country are mentioned.

After receiving a country with serious problems in all areas, and an economy in decline, he managed to get for many millions of people water and electricity, but the infrastructure was neglected also inefficiency and corruption became serious problems.

Johannesburg is the economic capital of South Africa, with four million of inhabitants within the city area and 7 million people living in the Metropolitan Area. The city is the economic motor of the Subsaharan Africa.

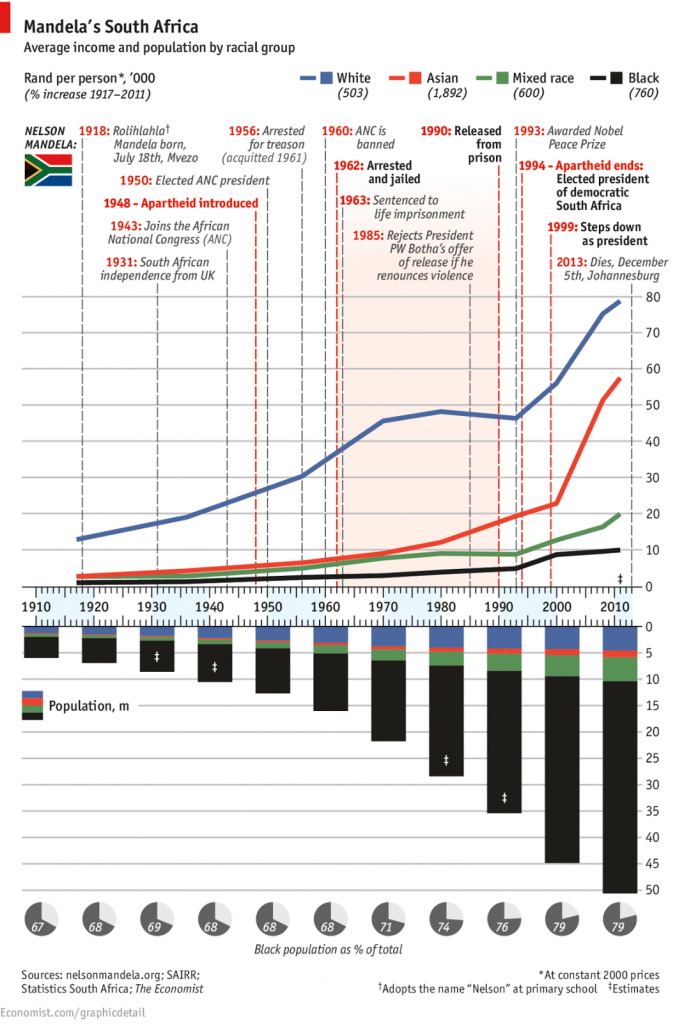

The gap between rich and poor is one of the highest in the world and some recent measurements show that is now higher than in the days of apartheid.

Inequality in South Africa is something that can be noticed strong enough, even during the time of the Mandela’s government, this does not mean that there were no major changes, this is related more to the facts that have to do with the perception of the inhabitants of the cities.

Even after eight years post-apartheid, you could witness on the streets of large and small cities, social inequality that comes from the policies of racial segregation made years ago, as a result, the city and its public space disappears and put in evidence physical and often also social imaginary barriers.

The street, according to the theorist David Harvey, “is a public space that has historically often been transformed by social action into the common of a revolutionary movement, as well as into a site of bloody suppression. There is always struggle over how the production of and access to public space and public goods is to be regulated, by whom, and in whose interests”1

The streets accordingly, as mentioned by Francisco Vergara “…is defined by how users activate it.”2 In this sense, The city of Johannesburg and many other South African cities have lost their streets.

The main character of the city of Johannesburg and its streets are dominated by old-impression of discomfort and difficulties of their people to leave together and share the same spaces with different types of races and ideologies that make up the country. This situation has been dominated still by this old perception of discomfort, insecurity, vulnerability of the citizens of Johannesburg, framed by the relationship of the problems of coexistence among different races and ideologies. During the post-apartheid era, just years before the 2010 World Cup, general thoughts on the streets as a social space in Johannesburg were simply related to the idea of ”forbidden zones” for anyone.

Private developers and city politicians have rejected some action in and within public spaces, working from the architectural envelope inward, creating the idea of offering comfort from a “safe cocoon”.

Many architects are attempting to convince developers and politicians to create some connectivity to the street, but not very successfully, at least not in the reconnection of existing urban areas. Some of these exercises results in experiments which have successfully created isolated and beautiful spaces, but end-up increasing the limits of the “safe cocoon” moving towards to the concept of “urban cocoon” where the street becomes an extension of the “safe cocoon envelope” where people feel safe and secure but the reality is to experience the street as defined by Harvey, has died. The welfare of the people are misinterpreting as an embodiment of exclusive benefits and convenience that involves the concept of “cocoon”. When it relates to the poorest people, is basically to provide basic needs, but still isolated and reluctant.

The problem here is not a misunderstanding between financial profitability and economical feasible, is about what reasons keep some developers thinking in a immediately profitability and not and economical feasibility that with time becomes even more profitable based in the comfort and welfare of the inhabitants.

The World Cup 2010 in South Africa, made a great impact in the way ZA recognize their cities and their spaces. The influence of visitors during that time, people without prejudice, and the great impact on the infrastructure throughout the country, especially the creation of new urban spaces, such as beachfront in Durban connecting the stadium with a track walking to the beach, the bus system integrated in Johannesburg and Cape Town, which was used by tourists without any concern or caution and the new generation of South Africans who fought against their fears and concerns.

At the same time, years before the World Cup, the new generations of Joburgers have opened their “back doors” to new activities based on the concept of ”secure envelop”, they are trying to bring people to the street again, starting with the creation of public spaces from the interior of the buildings, and thus, the notion of getting back on the street the inhabitants of the city, the street then becomes an extension of these spaces.

Young developers have taken the old buildings in different areas in Johannesburg and adapted from an easy and friendly way to create those urban spaces that have been lost in the time of the revolutionary and post- apartheid era. These developers have understood well that affordability becomes a financial return over the time, and one of the main rules is to keep the Mandela’s vision alive: All people from all different races together and sharing their own country.

1. Harvey, D. 2011. Rebel Cities. 1st Edition. Verso: New York – London.

2. Vergara, F. 2013. The Contested Space in Santiago: Clash Between Citizens and Government within the Civic District. Democracities.

| Gustavo Triana |