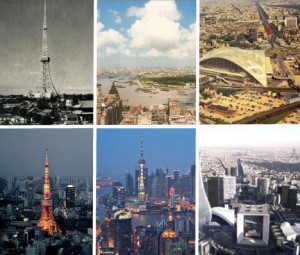

Unlike conventional wisdom, not only architecture, urban development or landscape design can be approached from economic analysis; it is also that economic analysis can provide a sound perspective, especially if sustainability is to be a guiding principle. This may seem paradoxical since economic development and growth, as we know them, have been blatantly unsustainable.

Sustainability overall is about the permanence of processes – something is sustainable because it can be sustained throughout time. On the basis of economic theory, sustainability is a capital transfer between present and future generations. Yet, capital is far from being a mechanistic notion of man-made or physical capital; it is also social capital, human capital, and natural capital.

Under the sway of the last four decades of economic thought, a pervasive idea is evolving: the need to redefine prosperity, to recognise that a significant number of consumption and production patterns cannot be sustained without affecting the welfare of future generations and (potentially) basic balances in the Biosphere that could threaten life itself and its diversity. The concept of quality of life suffers from an embarrassing richness of possibilities but what kind of circumstances provide good conditions under which to live? What makes a life a good one for the person who lives it? What makes life a valuable one? And should not this be relevant for architects?

Despite what most people would reckon, economic analysis could provide some answers to some of these questions. It’s not just a question, though, of redefining prosperity on the basis of the absence of growth (or even the so-called ‘de-growth’); it’s also a matter of redefining growth itself, since growth has proved to be a driver for prosperity in many contexts.

To put it this way, the question is not so much whether to grow or not, but how it comes about. Growth based on inequality or environmental degradation, for instance, is notably unsound and undesirable. Yet, in many places and for many people, growth has been extraordinarily successful in ensuring prosperity and opportunity for a wide majority. Growth, prosperity, happiness are after all (perceived as) goods, from a mainstreaming perspective. If using the analogy between growth and happiness is not because one immediately leads to the other but rather because the quest for growth can sometimes prevent growth from being a source of prosperity in such a way as the search for happiness is very often a source of unhappiness.

Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel Prize Laureate in Economic Sciences (2002), presents our thinking process as consisting of two systems: thinking fast (unconscious, intuitive, almost effortless), and thinking slow (conscious, through deductive reasoning, and with significant effort).

We tend (want) to think the latter prevails over the former but we might be wrong. We often associate intuition with irrationality but it is not. On the other hand, the origin of much that we do wrong (as individuals or as an entire society), is also at the roots of what we do right.

Critical thinking, as we have discussed at IaaC, is about solving conflicts. The great game of life, for architects or alike, may not just be about reason versus intuition.

Let me pose some questions for you and feel free to comment on them.

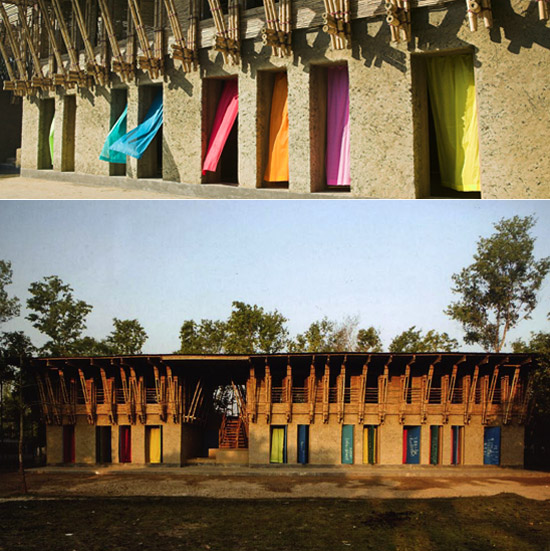

- It is very tempting to seduce ourselves, as architects or as anybody keen on architecture or otherwise involved in the design process that the answer to our problems lies with buildings. Do you actually believe you can separate buildings out from the infrastructure of cities and mobility of transit and the expectations and incentives of people?

- Why do people tend to believe that what is financially profitable (for developers) is not actually equivalent to economically feasible (positive impacts on social welfare)? How would you show that this does not necessarily have to be like this (but rather the opposite)?